Oil Twilight

Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy, Matthew R. Simmons, 2005

Here’s a sleeper only discovered after watching the recent Sundance channel apocalyptic documentary A Crude Awakening: the Oil Crash which heavily featured comments by energy expert Matthew Simmons.

A Crude Awakening makes some startling revelations about alternate energy sources. Hydrogen fuel is 50 years away from solving the problems of production, storage, and distribution. Hydrogen today requires five times the energy to produce that it supplies. If all automobiles in the world were replaced by hybids tomorrow, the oil supply would extend another two years at best. Replacing current electric generation facilities with nuclear power would require the building of 10,000 nuclear generators that would run out of fuel in 10 years, far sooner than oil. Biofuels have the potential to replace only a negligible quantity of oil. The apocalyptic documentary points out that we are now dependent on oil not only for power, transportation, and heat, but for the very food supply needed (chemical fertilizers) to support our exploding population. Ironically, without oil, the crops needed to produce biofuel cannot be grown. Solar energy is virtually the only viable alternative, but solar energy will require massive investments in research to make it viable on a large scale. Today solar energy is half the efficiency of oil but will soon be as efficient to produce. Wind power is also economically viable but not on a large scale.

Without oil we may be reduced to the population and lifestyles that existed at the beginning of the 20th Century. But evolution only goes one way; forward. What will life look like without oil? If global warming doesn’t get us first, we’re about to find out.

A Crude Awakening openly accuses the Bush administrations of starting a very expensive war in Iraq simply to assure access to a continuing supply of Middle East oil. Oil at any cost. Future and continuing oil wars as oil becomes scarce are one of the forecasts of the documentary.

We have now come to understand that Sadam’s weapons cache was a figment of our brilliant intelligence imaginations. To the people who got us into the Iraq war, the important intelligence probably did not concern the mythical weapons at all but concerned the equally mythical 115 billion barrel proven Iraqi oil reserve. Yet the Kirkuk oil field was discovered in 1927 and is now 78 years old, poorly maintained, and damaged repeatedly by sabotage. It is very unlikely there is anything approaching 115 billion barrels of proven reserve oil in Iraq. Evidence from next door Kuwait is that the world’s best technology from Chevron-Texaco has been unable to revive production in old fields.

Matthew R. Simmons is an oil expert and an industry investment insider. His book does not deal with the environmental impact of oil consumption such as global warming see and here. In fact his only mention of environmentalists is to note their impact on U.S. oil exploration on both coasts and Alaska. No, here is an expert calling attention to the failure of other so called energy experts to understand much less predict the future of oil exploration, production, and demand beginning with the start of big oil after WWII. The failures of the experts to understand oil rivals the failures of the CIA to understand the world over the same period.

Abd al-`Azīz Āl Sa`ūd 1876-1953 First King of Saudi Arabia father of all kings

In the 1930′s oil sold at the unbelievable price of 10 cents a barrel. When oil stabilized at around $1 a barrel after WWII, experts predicted worldwide economic collapse if oil ever went above this level. The brief OPEC oil embargo of 1973 sent prices to $12 from which they continued to climb through the Iranian Revolution in 1979 to peak at $40 in 1980 after which it dropped into a $12-$20 range until 1998. Prices are now setting records above $80 a barrel. None of this was predicted and the impact on the world economy is unknown. So much for the experts.

If anything, we might conclude that oil is such a cheap energy source compared to anything else that demand is almost perfectly elastic, that is, demand continues to rise and is almost completely insensitive to the price. In the perhaps near future, not only price but armed conflict and force will determine who gets the remaining shrinking supply.

Pilgrims to Mecca were the major source of Saudi revenue before oil

This book focuses on oil reserves, particularly in Saudi Arabia and predicts a rapid decline in worldwide oil production that no price can remedy. No major oil discoveries have been made since 1969 when the Prudhoe Bay, Caspian Sea, and North Sea deposits were discovered. With modern exploration technologies including seismic surveying and computer modeling Simmons argues it is unlikely that there are large undiscovered reserves left somewhere in the world.

Saudi Arabia gets most of its oil from six super-giant oilfields led by Ghawar at 174 miles long and 16 miles wide by far the largest oil field in the world which has alone produced 55 billion barrels of oil to date. To tap these enormous super-giants, very few wells were drilled. To increase or decrease production, operators simply turned the values of these few wells. The American operators, knowing they would soon lose control of the fields to the Saudis greatly increased production starting about 1970. The Saudis took control of oil in 1979, producing through their giant national Saudi Aramco, the largest oil company in the world. Saudi Aramco is a world class company that still employs 8,000 western petroleum experts. Their technology is state of the art. Unfortunately, in 1982, Aramco and the oil ministry made the decision to keep production and reserves secret. Other OPEC members followed and today our knowledge of true production and reserves is limited.

As an example of the unintended consequences of this secrecy, in 1997 OPEC announced increases in quota for all members. A market myth grew to fill the data vacuum created by production secrecy that there was a glut of oil. By 1999, accompanied by an Economist cover article “Drowning in Oil”, prices plummeted. The resulting myths to explain the glut included secret oil reserves and lost tankers wandering the oceans. Oil experts arose everywhere including a company Petrologistics claiming to have spies in every oil port counting the movement of tankers. Petrologistics was one guy working out of his apartment over a bakery in Geneva.

We know that Saudi reserves, said to be 110 billion barrels in 1978 when American oil companies handed over control to Aramco, grew to 260 billion barrels by 1988. These figures have no substantiating details and were probably woven out of whole cloth. During this period, from 1978 to 1988 46 billion barrels had been produced. Simmons believes these almost 200 billion barrels of new proven oil reserves are imaginary. Simmons also notes these supposed reserve discoveries were all made before the technological breakthroughs of 3D seismic analysis. Of Aramco and Saudi oil secrecy Simmons notes:

To get to the truth of Saudi oil production and reserves, Simmons made a close study of more than 200 technical papers published by the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE). Many of these papers were written by Aramco scientists and engineers and Simmons wondered why they were allowed to be published when careful reading would contradict official oil statements. I suspect the country is proud of this world leading company and feels its own prestige is enhanced by allowing its technologists to contribute and attend conferences.

You would have to be a specialist to understand most of these papers although Simmons does his best to educate us in the fundamentals of oil production and geology and to summarize and translate the technical papers but its still tough going unless you have a background in petroleum and geology. Greatly simplified, oil is found underground under high pressure. The pressure is sufficient to force the oil to the surface through vertical wells. If oil is overproduced, the pressure drops and there is a risk of oil being lost. To maintain pressure, water is injected via water injection wells. In 1956 40,000 barrels of water per day were being injected. By 1998 12 billion barrels a day were being injected into the two biggest fields. The initial water came from salt water aquifers. Starting in the 70s salt water from the Persian Gulf was piped to the fields for injection. As oil is depleted, more and more water is mixed with the oil extracted. The ratio of oil to water varies but recently about 1/3 has been water. Special processing is required to remove the salt water from the oil. To maintain production Aramco has done extensive horizontal drilling out from the main vertical wells. Care must be taken not to drill through fissures which might water out the well. Papers also describe insoluble tar layers encountered and studies of the effects of changing pressure on seismic activities (narrowing or widening of fissures). These 200 papers, covering research and events over all the major oil fields of Saudi Arabia paint a picture of maturing fields and ever increasing problems trying just to maintain production.

These papers report problems with production consistent with aging oil fields near the end of their productive life. They wrestle with the major problems: When will the giant field water out leaving billions of barrels of oil still in place? Can new technologies recover the oil left behind? What would be the cost of new technology? Can a few remaining years be stretched to a few decades? Simmons major conclusions rely on two factors known to be true outside of secret OPEC and Russia:

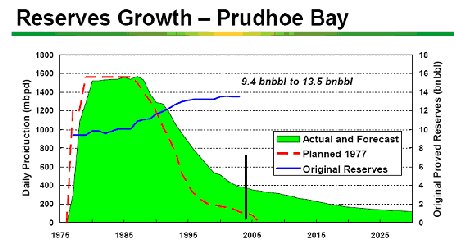

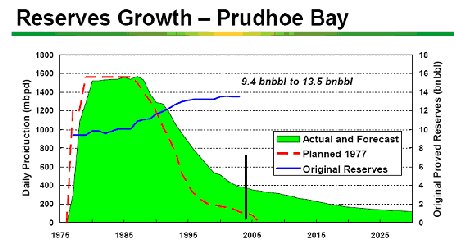

First, Eight super giant oilfields including Prudhoe Bay fields and North Seas fields have exhibited the same lifetime production pattern of increased production followed by the peak followed by a decline toward zero. The time frame of useful productivity is typically twenty years with the sole exception of Slaughter in Texas that has lasted sixty years and is still producing. Typical are reserve estimates from Prudhoe Bay. Aramco’s super giant fields have been in production for fifty years.

Second, no giant or super giant oil fields have been discovered since 1969 despite improved exploration technology. That is long enough with enough serious effort to project that the era of discovering giant oil fields is past. These last discovered giants all quickly reached their maximum production and then plummeted to enter secondary or tertiary production phases which is much more expensive and produces far less oil. Simmons believes Saudi and other Middle East production is in decline or soon will be.

The Saudis themselves have periodically increased production to stabilize worldwide oil supplies, for example after the Iranian revolution and resulting drop in Iranian production, and during Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, the gulf war, and oil disruption in Kuwait. Simmons gives elaborate explanations how increased production from Saudis super giants has damaged the fields, increasing the difficulty of future extraction, and reducing the amount of oil that will ever be extracted from these fields. This is called the risk of overproduction.

Simmons does not believe Aramco can increase production to meet further shortfalls in production elsewhere but most experts naively believe the Saudis can produce any amount they choose. Oil production in much of the world, including the U.S. where production peaked in 1970 is in decline. Where will the oil come from to meet increased demand even in the next few years? Simmons doesn’t know.

Simmons also points to the social impact of oil on producing countries. There were 4 million Saudis in 1970 when the price of oil starting climbing rapidly. The Saudis were able to greatly improve the standard of living for their citizens with subsidized or free social services. Unfortunately, their Wahhabist brand of Islam encouraged birth with an average of 6.3 children per household resulting in a population explosion approaching 30 million today. Even at today’s prices and levels of production oil revenue per Saudi is one fifth what it was in 1970. Oil and petrochemicals dominate the Saudi economy and neither require much labor. Without developing other sources of employment, the country is left with massive unemployment and the few jobs that exist are often taken by foreign nationals who are willing to work at menial jobs Saudis are unwilling to take. But even sophisticated Norway, huge beneficiary of North Sea oil, will need to plan carefully for when the oil runs out.

Here’s a sleeper only discovered after watching the recent Sundance channel apocalyptic documentary A Crude Awakening: the Oil Crash which heavily featured comments by energy expert Matthew Simmons.

A Crude Awakening makes some startling revelations about alternate energy sources. Hydrogen fuel is 50 years away from solving the problems of production, storage, and distribution. Hydrogen today requires five times the energy to produce that it supplies. If all automobiles in the world were replaced by hybids tomorrow, the oil supply would extend another two years at best. Replacing current electric generation facilities with nuclear power would require the building of 10,000 nuclear generators that would run out of fuel in 10 years, far sooner than oil. Biofuels have the potential to replace only a negligible quantity of oil. The apocalyptic documentary points out that we are now dependent on oil not only for power, transportation, and heat, but for the very food supply needed (chemical fertilizers) to support our exploding population. Ironically, without oil, the crops needed to produce biofuel cannot be grown. Solar energy is virtually the only viable alternative, but solar energy will require massive investments in research to make it viable on a large scale. Today solar energy is half the efficiency of oil but will soon be as efficient to produce. Wind power is also economically viable but not on a large scale.

Without oil we may be reduced to the population and lifestyles that existed at the beginning of the 20th Century. But evolution only goes one way; forward. What will life look like without oil? If global warming doesn’t get us first, we’re about to find out.

A Crude Awakening openly accuses the Bush administrations of starting a very expensive war in Iraq simply to assure access to a continuing supply of Middle East oil. Oil at any cost. Future and continuing oil wars as oil becomes scarce are one of the forecasts of the documentary.

We have now come to understand that Sadam’s weapons cache was a figment of our brilliant intelligence imaginations. To the people who got us into the Iraq war, the important intelligence probably did not concern the mythical weapons at all but concerned the equally mythical 115 billion barrel proven Iraqi oil reserve. Yet the Kirkuk oil field was discovered in 1927 and is now 78 years old, poorly maintained, and damaged repeatedly by sabotage. It is very unlikely there is anything approaching 115 billion barrels of proven reserve oil in Iraq. Evidence from next door Kuwait is that the world’s best technology from Chevron-Texaco has been unable to revive production in old fields.

Matthew R. Simmons is an oil expert and an industry investment insider. His book does not deal with the environmental impact of oil consumption such as global warming see and here. In fact his only mention of environmentalists is to note their impact on U.S. oil exploration on both coasts and Alaska. No, here is an expert calling attention to the failure of other so called energy experts to understand much less predict the future of oil exploration, production, and demand beginning with the start of big oil after WWII. The failures of the experts to understand oil rivals the failures of the CIA to understand the world over the same period.

Abd al-`Azīz Āl Sa`ūd 1876-1953 First King of Saudi Arabia father of all kings

In the 1930′s oil sold at the unbelievable price of 10 cents a barrel. When oil stabilized at around $1 a barrel after WWII, experts predicted worldwide economic collapse if oil ever went above this level. The brief OPEC oil embargo of 1973 sent prices to $12 from which they continued to climb through the Iranian Revolution in 1979 to peak at $40 in 1980 after which it dropped into a $12-$20 range until 1998. Prices are now setting records above $80 a barrel. None of this was predicted and the impact on the world economy is unknown. So much for the experts.

If anything, we might conclude that oil is such a cheap energy source compared to anything else that demand is almost perfectly elastic, that is, demand continues to rise and is almost completely insensitive to the price. In the perhaps near future, not only price but armed conflict and force will determine who gets the remaining shrinking supply.

Pilgrims to Mecca were the major source of Saudi revenue before oil

This book focuses on oil reserves, particularly in Saudi Arabia and predicts a rapid decline in worldwide oil production that no price can remedy. No major oil discoveries have been made since 1969 when the Prudhoe Bay, Caspian Sea, and North Sea deposits were discovered. With modern exploration technologies including seismic surveying and computer modeling Simmons argues it is unlikely that there are large undiscovered reserves left somewhere in the world.

Saudi Arabia gets most of its oil from six super-giant oilfields led by Ghawar at 174 miles long and 16 miles wide by far the largest oil field in the world which has alone produced 55 billion barrels of oil to date. To tap these enormous super-giants, very few wells were drilled. To increase or decrease production, operators simply turned the values of these few wells. The American operators, knowing they would soon lose control of the fields to the Saudis greatly increased production starting about 1970. The Saudis took control of oil in 1979, producing through their giant national Saudi Aramco, the largest oil company in the world. Saudi Aramco is a world class company that still employs 8,000 western petroleum experts. Their technology is state of the art. Unfortunately, in 1982, Aramco and the oil ministry made the decision to keep production and reserves secret. Other OPEC members followed and today our knowledge of true production and reserves is limited.

As an example of the unintended consequences of this secrecy, in 1997 OPEC announced increases in quota for all members. A market myth grew to fill the data vacuum created by production secrecy that there was a glut of oil. By 1999, accompanied by an Economist cover article “Drowning in Oil”, prices plummeted. The resulting myths to explain the glut included secret oil reserves and lost tankers wandering the oceans. Oil experts arose everywhere including a company Petrologistics claiming to have spies in every oil port counting the movement of tankers. Petrologistics was one guy working out of his apartment over a bakery in Geneva.

We know that Saudi reserves, said to be 110 billion barrels in 1978 when American oil companies handed over control to Aramco, grew to 260 billion barrels by 1988. These figures have no substantiating details and were probably woven out of whole cloth. During this period, from 1978 to 1988 46 billion barrels had been produced. Simmons believes these almost 200 billion barrels of new proven oil reserves are imaginary. Simmons also notes these supposed reserve discoveries were all made before the technological breakthroughs of 3D seismic analysis. Of Aramco and Saudi oil secrecy Simmons notes:

History has frequently shown that once secrecy envelops the culture of either a company or a country, those most surprised when the truth comes out are often the insiders who created the secrets in the first place. Such surprises may well have occurred within the ranks of Aramco and even at Saudi Arabia’s Petroleum Ministry.Don’t smoke your own dope!

To get to the truth of Saudi oil production and reserves, Simmons made a close study of more than 200 technical papers published by the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE). Many of these papers were written by Aramco scientists and engineers and Simmons wondered why they were allowed to be published when careful reading would contradict official oil statements. I suspect the country is proud of this world leading company and feels its own prestige is enhanced by allowing its technologists to contribute and attend conferences.

You would have to be a specialist to understand most of these papers although Simmons does his best to educate us in the fundamentals of oil production and geology and to summarize and translate the technical papers but its still tough going unless you have a background in petroleum and geology. Greatly simplified, oil is found underground under high pressure. The pressure is sufficient to force the oil to the surface through vertical wells. If oil is overproduced, the pressure drops and there is a risk of oil being lost. To maintain pressure, water is injected via water injection wells. In 1956 40,000 barrels of water per day were being injected. By 1998 12 billion barrels a day were being injected into the two biggest fields. The initial water came from salt water aquifers. Starting in the 70s salt water from the Persian Gulf was piped to the fields for injection. As oil is depleted, more and more water is mixed with the oil extracted. The ratio of oil to water varies but recently about 1/3 has been water. Special processing is required to remove the salt water from the oil. To maintain production Aramco has done extensive horizontal drilling out from the main vertical wells. Care must be taken not to drill through fissures which might water out the well. Papers also describe insoluble tar layers encountered and studies of the effects of changing pressure on seismic activities (narrowing or widening of fissures). These 200 papers, covering research and events over all the major oil fields of Saudi Arabia paint a picture of maturing fields and ever increasing problems trying just to maintain production.

These papers report problems with production consistent with aging oil fields near the end of their productive life. They wrestle with the major problems: When will the giant field water out leaving billions of barrels of oil still in place? Can new technologies recover the oil left behind? What would be the cost of new technology? Can a few remaining years be stretched to a few decades? Simmons major conclusions rely on two factors known to be true outside of secret OPEC and Russia:

First, Eight super giant oilfields including Prudhoe Bay fields and North Seas fields have exhibited the same lifetime production pattern of increased production followed by the peak followed by a decline toward zero. The time frame of useful productivity is typically twenty years with the sole exception of Slaughter in Texas that has lasted sixty years and is still producing. Typical are reserve estimates from Prudhoe Bay. Aramco’s super giant fields have been in production for fifty years.

Second, no giant or super giant oil fields have been discovered since 1969 despite improved exploration technology. That is long enough with enough serious effort to project that the era of discovering giant oil fields is past. These last discovered giants all quickly reached their maximum production and then plummeted to enter secondary or tertiary production phases which is much more expensive and produces far less oil. Simmons believes Saudi and other Middle East production is in decline or soon will be.

The Saudis themselves have periodically increased production to stabilize worldwide oil supplies, for example after the Iranian revolution and resulting drop in Iranian production, and during Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, the gulf war, and oil disruption in Kuwait. Simmons gives elaborate explanations how increased production from Saudis super giants has damaged the fields, increasing the difficulty of future extraction, and reducing the amount of oil that will ever be extracted from these fields. This is called the risk of overproduction.

Simmons does not believe Aramco can increase production to meet further shortfalls in production elsewhere but most experts naively believe the Saudis can produce any amount they choose. Oil production in much of the world, including the U.S. where production peaked in 1970 is in decline. Where will the oil come from to meet increased demand even in the next few years? Simmons doesn’t know.

Simmons also points to the social impact of oil on producing countries. There were 4 million Saudis in 1970 when the price of oil starting climbing rapidly. The Saudis were able to greatly improve the standard of living for their citizens with subsidized or free social services. Unfortunately, their Wahhabist brand of Islam encouraged birth with an average of 6.3 children per household resulting in a population explosion approaching 30 million today. Even at today’s prices and levels of production oil revenue per Saudi is one fifth what it was in 1970. Oil and petrochemicals dominate the Saudi economy and neither require much labor. Without developing other sources of employment, the country is left with massive unemployment and the few jobs that exist are often taken by foreign nationals who are willing to work at menial jobs Saudis are unwilling to take. But even sophisticated Norway, huge beneficiary of North Sea oil, will need to plan carefully for when the oil runs out.

No comments:

Post a Comment