|

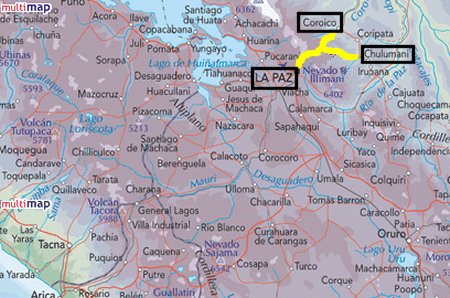

The Yungas Road is legendary for its

extreme danger.

In 1995 the

Inter-American Development Bank christened it as the "world's most

dangerous road". One estimate is

that 200-300 travelers are killed yearly along the road, or one

vehicle every two weeks. The road moreover

includes Christian crosses marking many of the spots where such

vehicles have fallen.

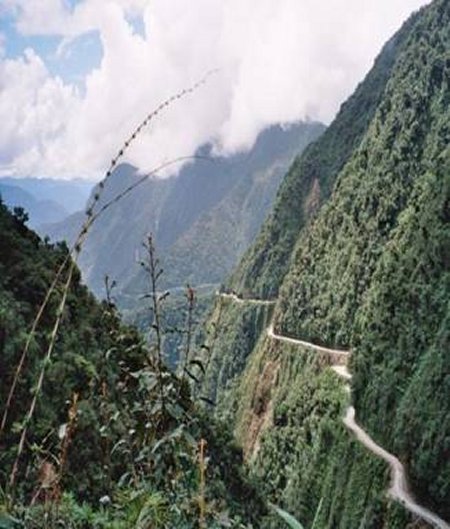

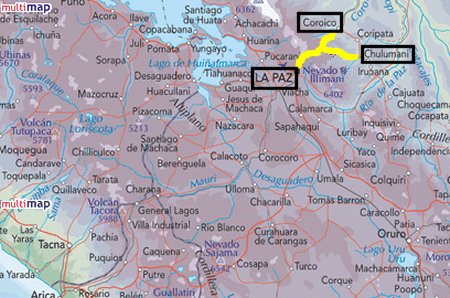

Upon leaving La Paz, the road first ascends up to around 5km, before

descending to 1079 ft (330 m), transitioning quickly from cool

altiplano terrain to rain forest as it winds through very steep

hillsides and atop cliffs.

The road was built in the 1930s during the Chaco War by Paraguayan

prisoners. It is one of the few

routes that connects the Amazon rainforest region of northern

Bolivia, or Yungas, to its capital city. However, an alternative,

much safer, road connecting La Paz to Coroico is nearing completion.

Because of the extreme dropoffs, single-lane width, and lack

of guardrails, the road is extremely dangerous. Further still, rain

and fog can make visibility precarious, the road surface muddy, and

loosen rocks from the hillsides above.

|

On July 24, 1983, a bus veered off the Yungas Road and into a

canyon, killing more than 100 passengers in what is said to be

Bolivia's worst road accident.

One of the local road rules specifies that the downhill

driver never has the right of way and must move to the outer edge of

the road. This forces fast vehicles to stop so that passing can be

negotiated safely. The danger of the road ironically though has made

it a popular tourist destination starting in the 1990s.

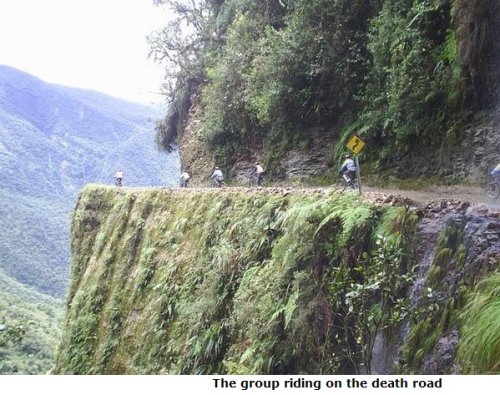

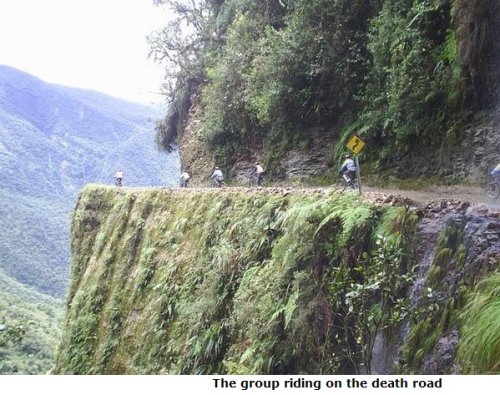

Mountain biker enthusiasts, in

particular, have made it a favorite destination for downhill biking.

Article One:

Bus crash kills 29 in Bolivia

Updated: 5:35 p.m. CT Oct 21, 2006

LA PAZ, Bolivia - A bus plunged off a mountain road in

central Bolivia early Saturday, killing 29 people and injuring 25,

police said.

The crash happened as the bus was attempting to make room for a

vehicle heading in the opposite direction along a narrow dirt road

near Chulumani.

The bus slipped off the edge and tumbled down the side of a cliff 50

miles east of the Bolivian capital of La Paz, said an official with

the regional police speaking on condition of anonymity according to

official policy.

The driver was among those killed in the crash.

The injured were taken to hospitals, while five of the dead remained

trapped in the wreckage. More deaths were possible given the

severity of injuries, the official said.

A bus wreck in August killed 24 after the driver apparently backed

over a cliff on another mountainous Bolivian road known as the

"Highway of Death" for its frequent fatal crashes.

Deadly wrecks are common in the Andean region, usually involving

inexpensive, unregulated buses traveling fast on poorly maintained

mountain roads.

Article Two:

The World's Most Dangerous

Road!

Written by Mark Whitaker,

BBC News, Bolivia

"Every year it is estimated 200 to 300 people die on a stretch of

road less than 50 miles long."

It seems perverse that one of the main roads out of one of the

highest cities on Earth should actually climb as it leaves town.

But climb it does - just short of a lung-sapping five kilometres

(three miles) above sea level, where even the internal combustion

engine is forced to toil and splutter.

Then it pauses for a while on the snow-flecked crest of the Andes

before pitching - like a giant white knuckle ride - into the abyss.

The road from Bolivia's main city, La Paz, to a region known as the

Yungas was built by Paraguayan prisoners of war back in the 1930s.

Many of them perished in the effort. Now it is mainly Bolivians who

die on the road - in their thousands.

In 1995, the Inter American Development Bank christened it the most

dangerous road in the world. And, as you start your descent, and

your driver whispers a prayer, you begin to see why.

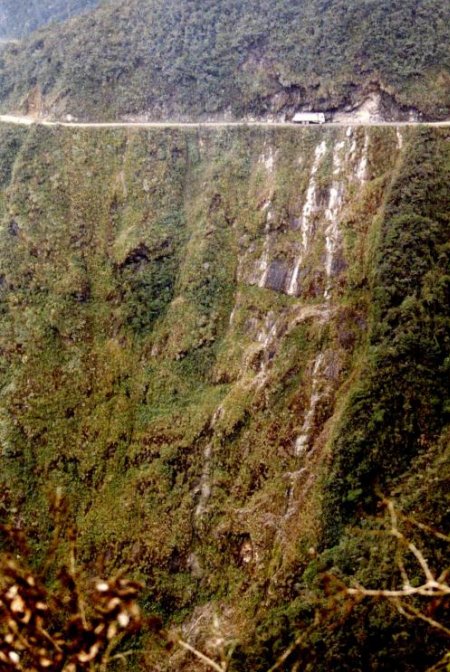

The bird's eye view is on the left, on the front seat passenger's

side, where the Earth itself seems to open up.

Crosses at the roadside mark the locations of fatal accidents.

A gigantic vertical crack appears. Way below, more than half a mile

beneath your passenger window, you can see - cradled between canyon

walls - a thin silver thread: the Coroico River rushing to join the

Amazon.

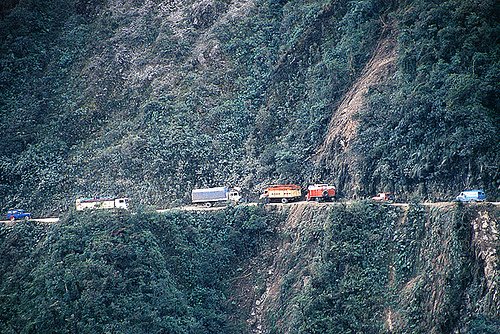

On the driver's side there is a sheer rock wall rising to the

heavens. There is no margin of error. The road itself is barely

three metres wide. That is if you can call it a road.

After the initial stretch to the top of the mountain it is just dirt

track. And yet - incredibly - despite no guard rails and hairpin

turns, it is a major route for trucks and buses.

Drivers stop to pour libations of beer into the earth - to beseech

the goddess Pachamama for safe passage.

Then, chewing coca leaves to keep themselves awake, they are off at

break-neck speeds in vehicles which should not be on any road, let

alone this one.

Perched on hairpin bends over dizzying precipices,

crosses and

stone cairns

mark the places where travelers' prayers went unheeded. Where, for

someone - the road ended.

But even these stark warnings are all too often ignored. As first

one - and then a second impatient motorist - overtook our car on the

ravine side of the road, my own driver - who hardly ever spoke a

word and only then in his native Aymara - intoned loudly, eerily and

in perfect English..."You will die."

It is not a rash prediction to make.

Extreme weather conditions make driving more hazardous.

Every year it is estimated 200 to 300 people die on a stretch of

road less than 50 miles long. In one year alone, 25 vehicles plunged

off the road and into the ravine. That is one every two weeks.

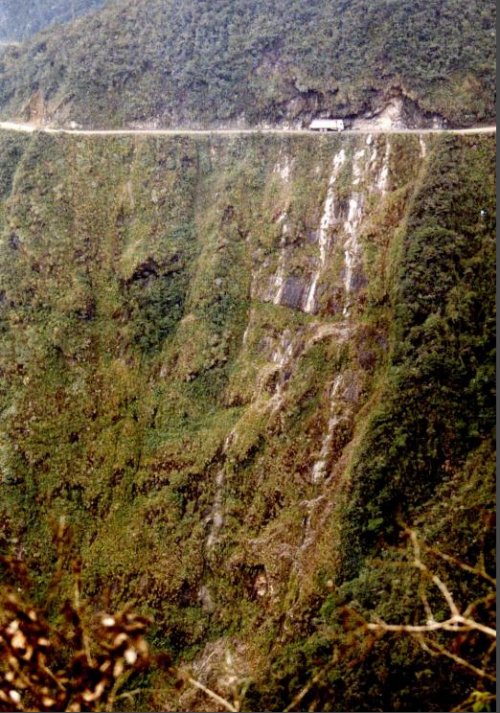

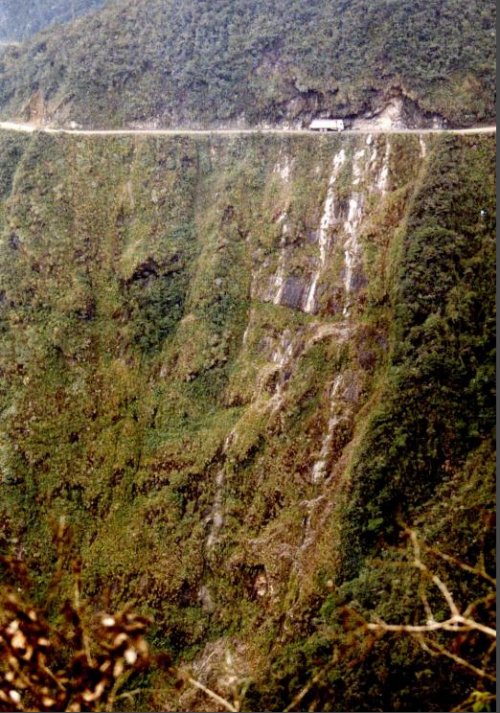

It is the end of the dry season in Bolivia. Soon the rains will come

- cascading down the walls of the chasm. Huge waterfalls will drench

the road - turning its surface to slime.

Then will come those heart-stopping moments when wheels skid and

brakes fail to grip. There are stories told of truckers too tired -

or too afraid - to continue, who pull over for the night, hoping to

see out an Andean storm. But they have parked too close to the edge.

And as they sleep in their cabs, the road is washed away around

them. Perched atop the cliff edge, this is not a good place to

drop off.

But for now the road is a ribbon of dust. Every vehicle passing

along it churns up a sandstorm in its wake.

Choking, blinding clouds obscure the way ahead. Around one hairpin,

a cloud of debris was beginning to clear.

Further down the road we passed a spot where a set of fresh tire

tracks headed out into the void

As it did, I could see people milling around in the road. Passengers

from one of the overloaded and decrepit buses which run the gauntlet

of this road.

It seemed at first that they had got off to stretch their legs,

while their driver argued with another vehicle coming in the other

direction about who should give way. (Reversing is not something you

undertake lightly on a cliff edge.)

It transpired instead though, that the bus driver was dying. Blinded

by the dust, he had run into the back of a truck. The bus's steering

column had gone through him - severing his legs.

There was nothing anyone could do. Mobile phones do not work here.

In any case, who would you call? There are no emergency services.

And no way of getting help through, even if any were to be found.

The bus driver bled to death.

We edged past the crumpled bus, and headed on.

Further down the road we passed a spot where a set of fresh tire

tracks headed out into the void. They told their own story.

High in the Andes, they are building a new road, a bypass to replace

the old one. But this is Bolivia, and already it has been 20 years

in the making.

Who knows when it will be complete? Until it is, people will have to

continue offering up their prayers, and taking their lives in their

hands on the most dangerous road in the world.

Article

Three:

Bolivia's

"Road of Death"

(This was taken from an article written

by a man who had finished traveling this road. Here he warns others

about the dangers of tourists traveling this road)

The North Yungas Road is hands-down

the most dangerous in the world for motorists.

It runs in the Bolivian Andes, 70 km from La Paz to Coroico, and plunges down almost 3,600 meters in an orgy of

extremely narrow hairpin curves and 800-meter abyss near-misses.

A fatal accident happens there every couple of weeks, 100-200 people

perish there every year.

Among the route there are many visible reminders of accidents,

wreckages of lorries and trucks lie scattered around at the

bottom... (read BBC article)

The buses and heavy trucks navigate this road, as this is the only

route available in the area. Buses crowded with locals go in any

weather, and try to beat the incoming traffic to the curves.

It does not help that the fog and vapors rise up from the heavily

vegetated valley below, resulting in almost constant fogs and

limited visibility. Plus the tropical downpours cause parts of the

road to slide down the mountain.

Apparently some companies make business on the road's dubious fame

by selling the extreme bike tours down that road. "Gravity Assisted

Mountain Biking" is one of them.

I read a scary account of a biking accident. The cyclist hit a rock going downhill and flipped over his handle

bars. He landed face first on the ground. As he lay writhing

in agony, a car coming around the curve missed hitting the man by a

mere 6 inches. The driver later said he swerved as much as he could,

but any more to the right and he feared his own car would go over

the edge!

If you are nuts enough to consider it, please be advised that you

will be only adding to the road hazards, as it's hard to spot a

cyclist on the road's hairpin curves, and your shrieks (as you fall

down the abyss) will disturb the peace and quiet of the villagers

nearby.

|

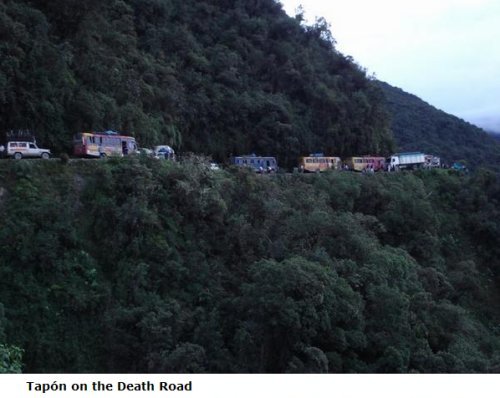

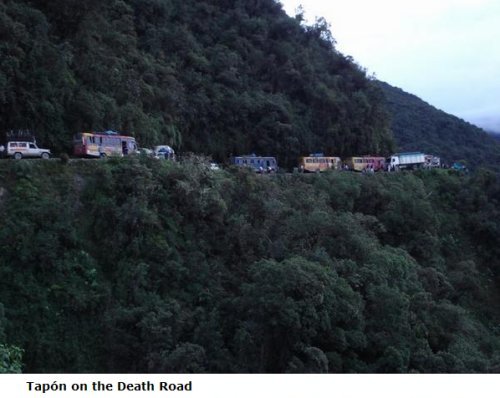

(I believe those stone cairns in the picture above

mark a spot

where vehicles have gone off the road.)

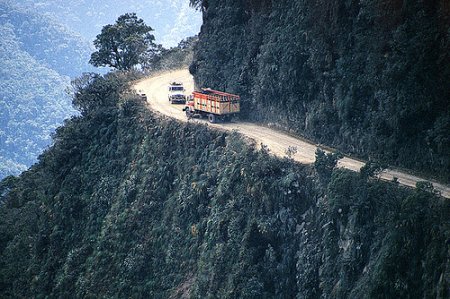

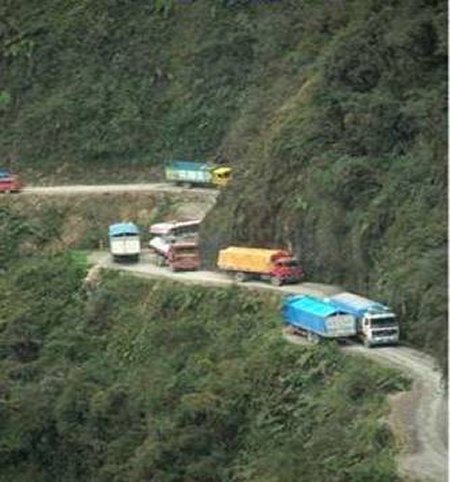

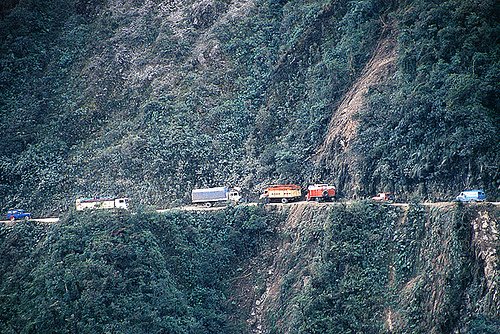

Two trucks passing - no room for error!

|

The Final Word:

A Letter regarding the Road of Death

Monday, November 27, 2006, 12:14:27 PM

To Mike Cannon,

I drove on the bolivia yungas road a few times when I lived in

this country. On this road, you drive on the left for the driver

to be on the downhill side and see exactly where you put your

wheels.

In many places, the road is too small. There is only one lane.

As a result, when the vehicle going down comes across a vehicle

coming up, it has to BACK UP to the passing area to allow the

climbing vehicle to proceed. It is very dangerous to back

up. Cars and trucks have actually fallen while trying to

back up because there is so little room for error!

It is then much better to be on the left hand side of the road

and lean outside the window to check where your wheels are: less

than 50 cms away (a mere 20

inches!!!) from the road's edge!

Needless to say that you do not open

the left door unless you want to risk falling down a few hundred

meters.

I am not sure I would ever have the guts to drive on this road

ever again!

|

|

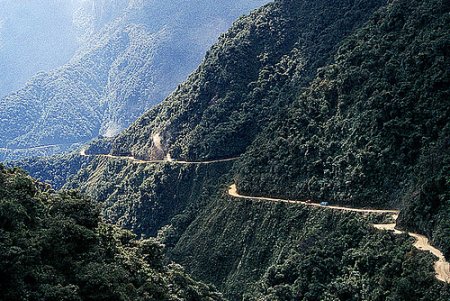

Down below across the valley is the winding Road of Death as seen from

the village of Coroico. Unbelievable.

Down below across the valley is the winding Road of Death as seen from

the village of Coroico. Unbelievable.

No comments:

Post a Comment